Home Page |

About Me |

Home Entertainment |

Home Entertainment Blog |

Politics |

Australian Libertarian Society Blog |

Disclosures

How Bad is Pan and Scan?

This version: 28 June 2003, previously published in DVD Now

Widescreen movies dominate the DVD format, with the two most common aspect ratios being 1.85:1 and 2.35:1, compared to the 1.33:1 (or 4:3) of a standard TV set. Some, however, have been converted to pan and scan versions to make them fill the screen of that very same standard TV.

Widescreen movies dominate the DVD format, with the two most common aspect ratios being 1.85:1 and 2.35:1, compared to the 1.33:1 (or 4:3) of a standard TV set. Some, however, have been converted to pan and scan versions to make them fill the screen of that very same standard TV.

In theory, this means that the left and right edges of the movie have been trimmed off to produce the narrower aspect ratio. Sometimes the action might be on, say, the left edge of the widescreen picture. In this case, the 4:3 frame would be 'panned' over to the left to make sure the action was captured.

We true DVD videophiles view pan and scan cuts of widescreen movies with scorn. We want to create the cinema experience in our own homes, and this includes seeing the movie in the same format as the theatrical exhibition, that is, in its original widescreen format. So, naturally, pan and scan DVD releases have attracted a great deal of criticism.

After all, if you lop the edges off 2.35:1 movie to make it 4:3, you are tossing out 43% of the original picture. For a 1.85:1 movie you lose 'only' 28%. We can see this with Figures 1 and 2, the same scene from the flip sides of Jack Frost (which is widescreen on one side, and pan and scan on the other).

But is this bad reputation entirely justified?

Indeed, are all 'pan and scan' movies really pan and scan? For example, A Bug's Life was entirely computer generated. The 4:3 version is not the widescreen movie chopped off at the edges. It was simply recomposited from start to end, with some horizontal cropping and the addition of more foreground and background according to the artistic judgement of the editors.

Indeed, are all 'pan and scan' movies really pan and scan? For example, A Bug's Life was entirely computer generated. The 4:3 version is not the widescreen movie chopped off at the edges. It was simply recomposited from start to end, with some horizontal cropping and the addition of more foreground and background according to the artistic judgement of the editors.

Obviously this isn't an option with filmed live action ... or is it? Film stock has got better over the years. In the early days of widescreen cinema it was necessary to use an anamorphic lens (which squeezed a picture sideways) so that all the resolution of a 35mm film frame could be used. But with Super 35 and similar films, the resolution is high enough that a regular spherical lens can be used, producing an undistorted 1.37:1 print. The widescreen print is prepared by masking off the bottom and top of each frame (that is, the original print is chopped for theatrical presentation!)

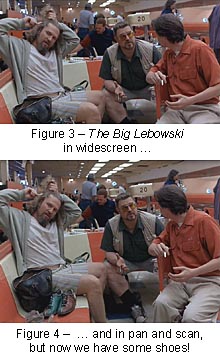

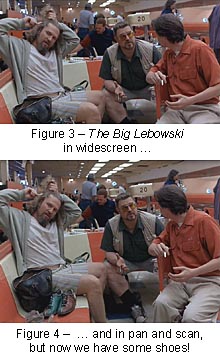

What this means is that quite a few modern movies are, Bug's Life fashion, recomposed from the original for the pan and scan versions. Look at Figures 3 and 4, screen shots from the flipside versions The Big Lebowski. What do you lose in the 'pan and scan' version? Just a little of Steve Buscemi's elbow. But the widescreen version crops out John Goodman's shoes and most of the overhead lights.

Even the more difficult to handle 2.35:1 aspect movies like Gattaca (actually, it's 2.38:1) can scrub up reasonably well as shown in Figures 5 and 6. Yes, you lose a little of Ethan Hawke's back and some wall space, but you gain hands and more at the bottom of the 4:3 version. Now at least we know what they're looking at.

Other movies in dual format that I have examined and appear to use cropping for both the pan and scan and widescreen versions are Madeline, Sleepers, and Big Daddy.

Other movies in dual format that I have examined and appear to use cropping for both the pan and scan and widescreen versions are Madeline, Sleepers, and Big Daddy.

So, forgive me, but a pan and scan rendition of a movie is not necessarily its death knell.

Finally, consider The Truman Show. The Region 1 version is in non-anamorphic NTSC and presented in an aspect ratio of 1.64:1. The Region 4 version is anamorphic PAL and presented at 1.79:1. The flatter aspect ratio (and consequent ability to render it anamorphically) of the PAL version comes at the expense of trimming nearly five per cent off the top and another five per cent from the bottom of each frame.

But I know which one I prefer to watch on my widescreen TV.

© 2001 by Stephen Dawson

Widescreen movies dominate the DVD format, with the two most common aspect ratios being 1.85:1 and 2.35:1, compared to the 1.33:1 (or 4:3) of a standard TV set. Some, however, have been converted to pan and scan versions to make them fill the screen of that very same standard TV.

Widescreen movies dominate the DVD format, with the two most common aspect ratios being 1.85:1 and 2.35:1, compared to the 1.33:1 (or 4:3) of a standard TV set. Some, however, have been converted to pan and scan versions to make them fill the screen of that very same standard TV.

Indeed, are all 'pan and scan' movies really pan and scan? For example, A Bug's Life was entirely computer generated. The 4:3 version is not the widescreen movie chopped off at the edges. It was simply recomposited from start to end, with some horizontal cropping and the addition of more foreground and background according to the artistic judgement of the editors.

Indeed, are all 'pan and scan' movies really pan and scan? For example, A Bug's Life was entirely computer generated. The 4:3 version is not the widescreen movie chopped off at the edges. It was simply recomposited from start to end, with some horizontal cropping and the addition of more foreground and background according to the artistic judgement of the editors.

Other movies in dual format that I have examined and appear to use cropping for both the pan and scan and widescreen versions are Madeline, Sleepers, and Big Daddy.

Other movies in dual format that I have examined and appear to use cropping for both the pan and scan and widescreen versions are Madeline, Sleepers, and Big Daddy.