My posts on 3D are all over the place. I had a total loss of confidence in my earlier work on passive 3D. And I’ve been busy. So lately I’ve been in hiatus here while I try to make sense of things.

So now I’m back, and I’m proposing to do a series of relatively short posts examining bits of passive TV. Unfortunately even at this stage I’m still left with questions as to how passive TVs operate. Still, this is where I’m at.

First, the basics. 3D displays work by feeding one image to one eye, and a related but different image to the other. These represent the slightly different views that your eyes get on anything that is out there. You brain knits these together to create a single image, but one with this magical ‘depth’ property. It’s like there’s an overlay map on this indicating the relative distances between the different objects that you focus upon.

Thus far there are two main ways in consumer technology for delivering these two images. One is by filling the screen with the left eye image and allowing only the left eye to see it, then repeating for the right eye. This is so-called ‘Active 3D’

, because you wear glasses that have liquid crystal shutters that open and close, synchronised with what the TV is showing.

The other way is so-called ‘Passive 3D’. In this both the left and right eye images are shown on the screen at the same time. You wear passive glasses (ie. they do not change their state) which allow the left eye to see only the parts of the screen intended for it, and the right eye to see only its parts of the screen.

The technique is circular polarisation, with the two lenses polarised differently, so as to match the polarisation of the parts of the screen they are intended to see.

Which parts of the screen though?

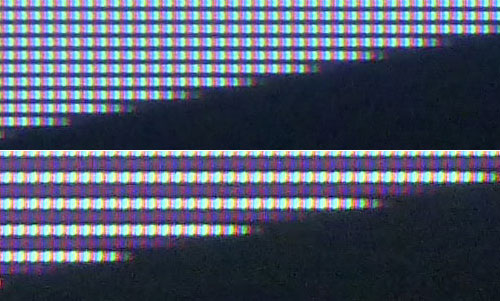

Each of the 1080 horizontal rows of pixels on the screen are polarised. The top row (which I will call line 1) is polarised such that its content will pass through the left eye lens, and can thus be seen by the left eye. Likewise for lines 3, 5, etc through all the odd-numbered lines. The second row is polarised the other way, so that to a viewer wearing the 3D glasses its contents can be seen only by the right eye.

Note that this system has this effect regardless of whether the material being shown on the screen is 3D.

So if you are watching something 2D, in 2D mode on a passive 3D TV, then if you were to don the 3D glasses diagonal lines would get visibly jaggie if you are close enough. Here is a close up photo. This is the same line photographed from the same position, but the top was photographed directly from the screen, while the bottom was through one of the passive glasses lenses:

Coming soon: Part 2 – Line allocation