Statistician William M Briggs features on his excellent blog an occasional series of posts dedicated to proving that modern music is crap

, at least in comparison to older music. Although there are hints that The Beatles represent the nadir of the art.

I like to think that they’re largely tongue-in-cheek, but sometimes fear that they aren’t.

On his most recent (‘More Proof Music Is Growing Worse‘) I offered a very long comment which I might as well reproduce here, thus:

Briggs, tsk, tsk. Many studies you report on here you properly shred for methodological errors. But not this one. Are we seeing just a little confirmation bias here?

The first place I’d start is with the source of the raw data used in the analysis. This is ‘The million song dataset’ (pdf) referenced in Note 14 of the study, ‘Measuring the Evolution of Contemporary Western Popular Music’.

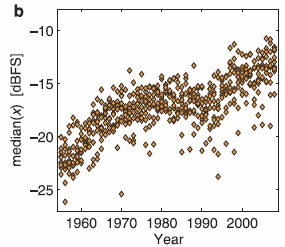

But I have grave doubts about its validity simply from inspecting the loudness vs year graph you reproduced (see right).

But I have grave doubts about its validity simply from inspecting the loudness vs year graph you reproduced (see right).

The vertical scale on this is ‘dBFS’ which stands for decibels referenced to the full scale (thus the negative numbers on the scale, since full scale is 0). A decibel is a unit of measure for logarithmic ratios. When dB is used as a unit for actual loudness, it is properly called dBSPL (Sound Pressure Level) and the reference for the ratio calculation is an extremely low power level, just barely audible.

With dBFS the FS is the 0 on the digital meter. Unlike analogue, this is a hard limit. In a 16 bit system, say, an audio level of greater than 32,767 cannot be recorded. It will simply be truncated to that.

Now, looking at the graph we can see that the database has songs going back into the 1950s. We know that commercial digital recording did not start until the early 1970s (probably using the Soundstream 16 bit, 50kHz system). We know that the first digital recording of popular music was made in 1979. We also know that digital recording of popular music did not become ubiquitous until at least the late 1980s, and probably into the early 1990s.

So we know that all the songs in the first half the database were analogue recordings, later transferred to digital by unknown engineers using unknown criteria. Did they transfer at a low level to try to keep tape noise to a low level? Did they transfer at some semi-random level within the number space available on a 16 bit system? Did they transfer at a high level, dynamically compressing the music to fit, or even unknowingly clipping it?

What we do know is that CDs have been getting louder (is in, average level) over time … even for the same performances of the same songs! In general when a ‘remastered’ CD of older music is released, its average level is higher than the earlier version. This can actually involve the mastering engineer applying some dynamic range compression in order to get the average level up without breaching the hard 0dBFS limit.

But all these are engineering techniques, and have nothing whatsoever to do with the songs themselves, merely the way they are commercially presented.

In support of this explanation, inspect the graph. The curve shows a roughly linear rise from ~1955 to ~1975. It is then flat to ~1995 and then starts rising again.

In 1955 there were effectively no post-recording dynamic compression tools. Listen, for example, to Swing Around Rosie (Rosemary Clooney and the Buddy Cole Trio, 1958) or Kind of Blue (Miles Davis, 1959) for recordings which are clearly technically challenged due to the equipment of the day, but are nonetheless lively because they are totally uncompressed.

But dynamic compression systems were developed and deployed from this time forward and throughout the sixties. The main consumer medium — vinyl — and the limited quality of mainstream playback equipment favoured the use of dynamic compression to allow clarity in the audio signal. A balance between purity and clarity would have been achieved by the early to mid-1970s, thus the plateau. By the mid-1990s, though, the ‘jukebox effect’ began to take hold as the CD became the predominant playback medium. This demanded that any random song should sound as loud (ie. short term average level) as the one preceding it in a jukebox. Or louder. Thus the escalating average levels.

An interesting study, perhaps, but one that must be taken with extreme care.