Subjective assessment of home entertainment equipment is important because there are characteristics of performance which aren’t well conveyed through measurements. I am not saying that these things aren’t captured by the measurements (thoroughly and carefully conducted); merely that few people glancing at a frequency response graph which shows an elevation of a couple of decibels in the two to six kilohertz region will realise that in practice, this means that these speakers will sound more forward and, sometimes, even a little more harsh, than speakers lacking this measurement.

But this should be approached humbly, and with due recognition of its limitations. I maintain that no-one can hear the difference between two accurate, properly operating amplifiers, working within their capabilities with regard to output and load. If someone hears a difference, then they are either fooling themselves, or one (or both) of the amps is not accurate, is not working properly, or is being overloaded in some way.

If you use low efficiency loudspeakers of high power handling capability to play music at a high level, you will get better sound with a more powerful amplifier than a low powered one. But again we are talking about them working within their capabilities.

Some, however, claim that they can hear these differences because the human ear is such a wonderfully sensitive instrument.

Wrong.

It is wrong because the human ear is not an instrument. It is indeed wonderfully sensitive (although less so that some animal ears). But it is no instrument.

By ‘instrument’ I, and I think those who make this claim, mean a device for measuring things. In fact, our ears — or more properly, our sound detection and interpretation mechanisms (which includes the relevant parts of the brain) are lousy at measurement. Because that is not their purpose.

Let me repeat that. Our ears and brains were not developed to give an accurate picture of the world about us. They were developed to give a tolerably accurate one.

Tolerably accurate means good enough to allow us to survive in our ancestral environments. That means that we need to be able to hear danger approaching and determine the direction from which it approaches.

This is not an open ended capability. It costs resources to make some aspect of an organism work better, so there is a trade-off between accuracy in hearing and other survival and reproductive capabilities, such as better eyesight or stronger legs or a more flexible brain.

Furthermore, the accuracy must be a trade-off against processing speed. The ears generate signals based on varying air pressure density in their vicinity. These signals are processed by a brain that has limits to its processing power (for the same reasons of the economy of an organism mentioned above). It takes shortcuts to derive the information it needs to help you stay alive.

Because it is far more useful to have ears that tell you a predator is stalking you from that direction instantly, even if they are wrong one time in a thousand, than it is to have perfectly accurate information five seconds later. For by then you may well be dead.

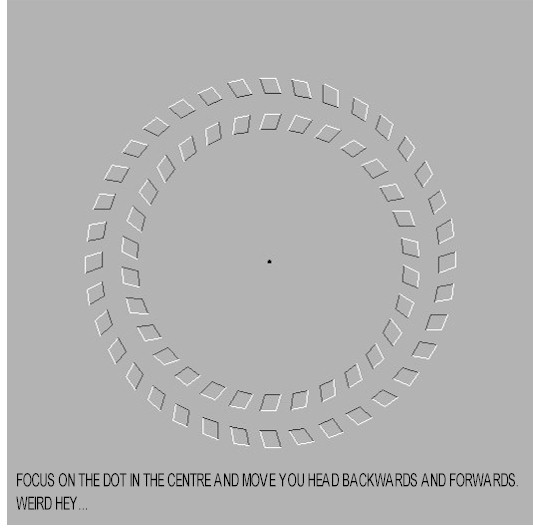

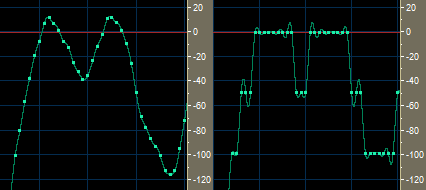

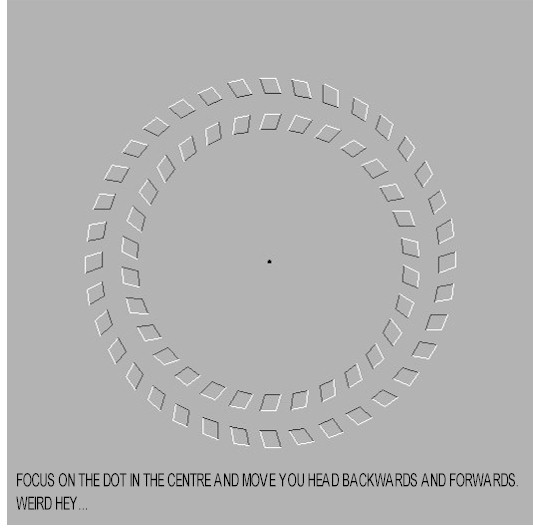

This is a bit hard to demonstrate with sound, so let’s look at a couple of visual examples which demonstrate how our seeing mechanisms let us down … if you think that they ought to clinically capture the world as it is. The bottom one has its instructions in the graphic. For the top one, just follow the apparent rotation for a moment as each purple dot flashes away in turn. Nothing awry there.

Now focus on the black cross. Maintain your centre of focus on that spot. Instead of the circling being due to the disappearance in turn of the purple dots, you will see a green dot circling. Keep watching that black cross. After a few seconds the purple dots will all disappear and all you will see is the green dot circling.

These optical illusions exploit vision processing shortcuts used by a brain to deliver us an actionable picture of the world right now, rather than an accurate picture of the world too late.

As for sound, thank goodness for our ears’ inaccuracies. Consider: if our ears gave a perfectly accurate aural picture of what’s out there, stereo and surround sound would not work. In the real world, something that makes a sound produces it all from one place, and it radiates outwards in all directions. With stereo and surround, we fake that with path lengths and delays and relative volume levels from multiple sources. And with good gear it can sound wonderfully convincing.

But it wouldn’t if our ears were good enough to measure with.

(I gathered the two graphics from emails sent to me a long time ago. The sources were not stated. If anyone owns these images and wants me to remove them or whatever, please contact me.)